The Alternative Film Culture of Fugitive Cinema

In the 1960s and 1970s, the film collective Fugitive Cinema injected Belgian cinema with a dose of political and social commitment. Fugitive did not only provide an alternative to the dominant film culture by making films, but also by promoting and distributing films that other distributors ignored.

By Gertjan Willems

More than Film Production

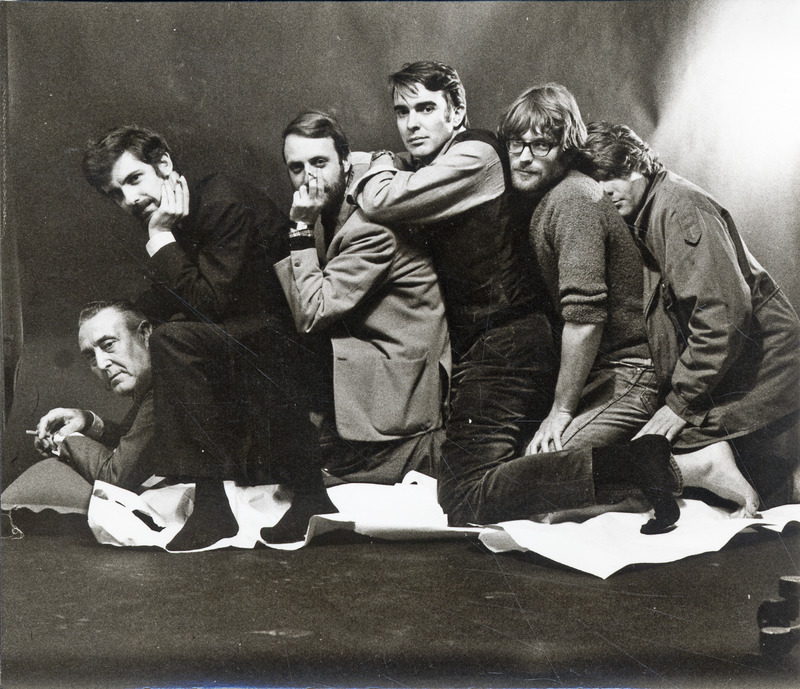

Together with a bunch of friends, Robbe De Hert (1942-2020) – the enfant terrible of Belgian film – founded Fugitive Cinema in 1966. The Antwerp-based film collective soon attracted filmmakers such as Patrick Le Bon and Guido Henderickx. They gained national and international fame with critical and socially committed films such as A Funny Thing Happened on my Way to Golgotha (1968), S.O.S. Fonske (1968) and Camera Sutra (1973). Formal experiments, including the collage-like use of archival, documentary and fiction footage reinforced the alternative character of the films, many of which can be seen as cinematic translations of the May 68 protests.

Film historian Philip Mosley, who wrote the only English-language monograph on Belgian cinema, describes Fugitive Cinema as a ‘powerful film unit, unique in Belgian cinema for its collectivist nonconformity’. This is how Fugitive Cinema is commonly characterized: as a collective of filmmakers. Like most other authors, Mosley focuses on the collective’s film productions and does not refer at all to its distribution activities. Yet these are essential for a better comprehension of Fugitive Cinema. In fact, Fugitive Cinema even developed a certain degree of vertical integration as the collection was also involved in a few film exhibition initiatives.

Cinema With a Smell

In 1971, De Hert co-founded Studio 2001, ‘the cinema with a smell’, as the film club’s tagline read. Located in an art gallery in Antwerp, Studio 2001 organized weekly screenings of Fugitive’s own productions and (mainly) other films they deemed artistically or socially valuable. The film club was soon absorbed into the cultural centre King Kong, again co-founded by De Hert.

The King Kong quickly became one of the hotspots of Antwerp’s alternative scene during the 1970s. The film club De Andere Film (‘The Other Film’) took care of the film programming. While research on the King Kong’s film programming (and on the King Kong in general) is lacking, Fugitive Cinema seems to have been closely involved through De Hert and other Fugitive members. This was also facilitated by the fact that Fugitive’s office was housed in the same building as the King Kong for a while, together with a number of other progressive cultural and political groupings.

Fugitive Cinema thus contributed to providing an alternative to Antwerp’s commercial film theatre market, which was dominated by Georges Heylen’s Rex concern. But it was in its role as a film distributor that Fugitive had the biggest impact on the formation of an alternative film culture in Belgium.

A Gathering Place of Outlaws

Already at the end of the 1960s, Fugitive Cinema started to develop its distribution activities. This was partly done out of necessity, as Fugitive found it difficult to find an appropriate distributor for its own productions. In 1969, Fugitive published its first distribution ‘catalogue’ (a few stencilled pages), in which its own short films were complemented with avant-garde films by other Belgian filmmakers, such as Roland Lethem and Jean-Marie Buchet.

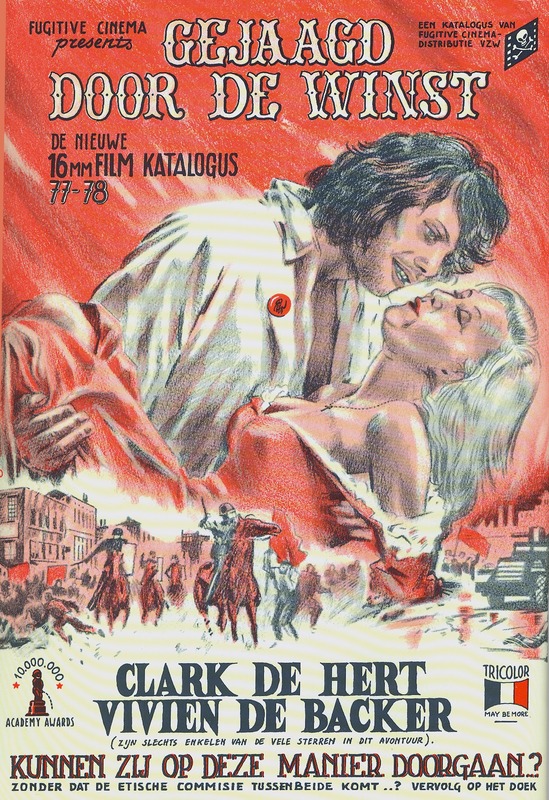

‘It was a curious collection of socially committed alongside anarchist-experimental films’, Fugitive recalled in its catalogue of 1978. ‘All these productions had one thing in common: they were in our catalogue because the existing distributors were not interested in our films, found them too difficult, too unconventional, too bad, or they simply did not dare to show them. Our catalogue thus became a gathering place of ‘outlaws’, who had only committed one crime: they were non-commercial. This crime, as you know, is punishable by starvation in our system.’

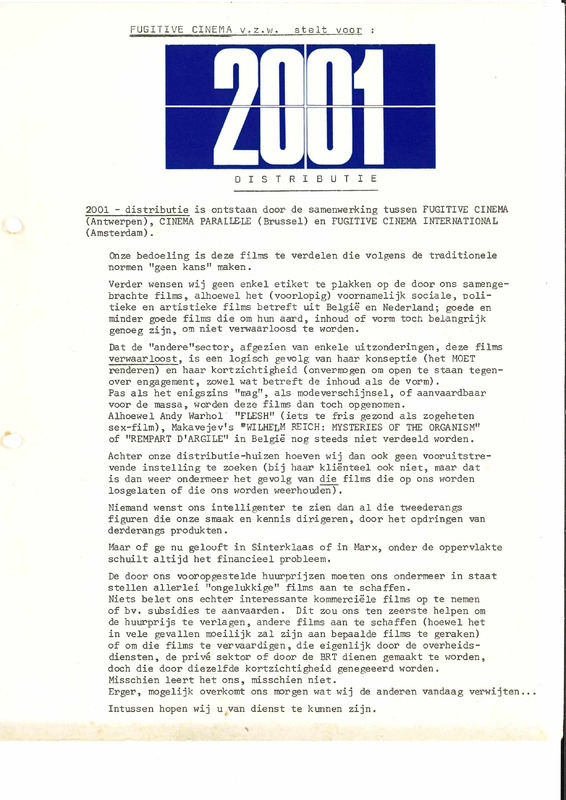

By the time these words were written in 1978, the number of films had increased from 25 short films to some 180 short and feature-length films. The selection was no longer limited to Belgian films alone. Many foreign films were excluded from the conventional film distribution system on the same grounds. The catalogue summarized the selection criteria as follows: ‘A conscious choice of non-commercial films: socially committed, frank, sometimes difficult and tricky, but all films that try to tell what others are trying to cover up.’ This resulted in a combination of experimental and avant-garde films, films focusing on topical issues of the 1970s (such as abortion and the political struggle in South America), and some key art films of the period, such as Wim Wenders’s Alice in den Städten (Alice in the Cities, 1974) and Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville’s Ici et ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere, 1976). These films mainly circulated in an alternative film exhibition circuit in Belgium, consisting of film clubs and social and political organizations.

True to the collectivist spirit of Fugitive Cinema, co-operation with other like-minded organizations was a key strategy from the early beginnings. Fugitive shared its catalogue with first the Brussels-based Cinéma Parallèle and then Cinélibre, which took care of the francophone part of the Belgian market, while Fugitive focused on the Dutch-speaking part. The Netherlands was served by the Amsterdam-based Fugitive Cinema Holland. For a short period, there had even been a German Fugitive spin-off, and there were many other national and international contacts and collaborations, such as with Chris Marker’s collective SLON in France. Fugitive Cinema was part of a complex and rapidly evolving transnational network of alternative distributors and other film organizations about which hitherto very little is known.

An Entangled History

Further research is needed to unravel the history of alternative film distribution and exhibition in Belgium. In the case of Fugitive Cinema, the study of its distribution activities is also essential to gain deeper insight into its film productions, and vice versa. Indeed, Fugitive’s production and distribution activities cannot be seen separately for several reasons: the distribution department was established in function of Fugitive’s film productions, several people were active in both departments (which were part of the same firm until 1979) and the combination of production and distribution activities fitted within Fugitive’s overall mission to provide an alternative within Belgium’s film culture at large.

The entanglement between Fugitive’s distribution and production activities is also clear from the militant tone they have in common, as well as from other shared rhetorical and stylistic features visible, for example, in the designs for catalogue covers and film posters. Sometimes, the connections go even further. In Camera Sutra (1973), images from Misère au Borinage (1934) are shown, accompanied by John Lennon’s song ‘Working Class Hero’ on the soundtrack. In this way, De Hert wanted to promote the enduring topicality of Joris Ivens and Henri Storck’s milestone in the history of social film. This was also done by including Misère au Borinage in Fugitive’s distribution catalogue and providing the film (for the first time, more than 35 years after its original release) with Dutch subtitles.

By explicitly paying homage to Misère au Borinage, De Hert positions Camera Sutra in a film historical tradition. The inclusion of Misère au Borinage in the distribution catalogue, then, indicates that Fugitive’s distribution activities can tell us a lot about the frame of reference for Fugitive’s own film productions. Indeed, while film historical contextualizations mostly rely on film analysis and biographical research (which films have the filmmakers seen, which films do they refer to?), these methods should in the case of Fugitive Cinema be complemented by a study of its distribution activities, as these offer a unique insight into which films the collective really deemed valuable. Of course, not all the films that were important for the Fugitive filmmakers were distributed by Fugitive Cinema, but some of the catalogues even include a list of ‘recommended films’ that were distributed by other companies.

While Fugitive Cinema is often reduced to its film productions, the above has hopefully made clear that it is necessary to pay equal attention to Fugitive’s distribution and exhibition activities. Fugitive played an important role in promoting an alternative film culture in Belgium, and its distribution and production activities were inherently interwoven. By taking such an integrated approach, we can come to a fuller comprehension of the collective’s meaning for the history of cinema in Belgium.

Further Research

On Cinema Belgica there is much more to discover about alternative film distribution and exhibition in Belgium. Some interesting topics for further research are:

- What kind of venues screened films distributed by Fugitive Cinema and Cinélibre? Were these only film clubs and other alternative exhibition venues, or also more commercially oriented film theatres? What about the geographical location of these venues? Were most of them located in Antwerp? Were there differences between cities and villages?

- The production and distribution departments of Fugitive Cinema were strongly interwoven. Do we see similar connections between distribution and production practices among other Belgian film organizations?

- Were certain films that first circulated within the alternative cinema circuit later taken up by major distributors or screened at more commercial venues?

- What other ‘alternative’ film distributors were active in Belgium, what was their identity and how did they relate to Fugitive Cinema? How were Fugitive Cinema and these other distributors related to international developments in distribution?

Other Sources and Data

Researchers who are interested in Fugitive Cinema and alternative film distribution and exhibition in Belgium, can also look at:

- FelixArchief: Archive of the City of Antwerp, which preserves the Fugitive Cinema Archive. Other archives where Fugitive Cinema documents can be found are the Letterenhuis and Amsab-ISG.

- BelgicaPress: digitized Belgian historical newspapers of the KBR/Belgian Royal Library.

- Cinema Context: Dutch online platform with detailed information on movies’ distribution patterns in the Netherlands.

- Cinematek: library catalogue of the Belgian Royal Film Archive.

- Media History Digital Library: key platform for media and film historians with digitized film magazines and trade journals.

Further reading

Quotes and sources used in this narrative:

- Eysakkers, H. (1976). Alternatieve film en alternatieve filmdistributie in België. De Andere Film.

- Fugitive Cinema (1978). Catalogus 78-79. Fugitive Cinema

- Fugitive Cinema (1991). 25 years Fugitive Cinema. Fugitive Cinema.

- Mosley, Ph. (2001). Split screen: Belgian cinema and cultural identity. SUNY Press.

More information on Fugitive Cinema:

- De Hert, R. (1983). Het drinkend hert bij zonsondergang. Het jungle boek van de Vlaamse film. Kritak.

- De Hert, R. (2003). Het drinkend hert in het nauw. Van Halewijck.

- De Poorter, W. (1984). Het idealisme van Fugitive Cinema. Ons Erfdeel, 27(2), 252-258.

- De Poorter, W. (1991). Vijfentwintig jaar Fugitive Cinema. Ons Erfdeel, 34(5), 778-779.

- Lietaer, L. (1991). 25 jaar Fugitive Cinema. Overzicht van een uniek stuk Vlaamse cinema [Unpublished licentiate’s thesis]. KU Leuven.

- Willems, G. (2020). Robbe De Hert: Beeldenstormer, publieksfilmer en promotor van de filmgeschiedenis. TMG Journal for Media History, 23(1-2), 1-24.

- Van Bos, I. (2013). De geschiedenis van Andere Sinema [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Antwerp.

More information on film exhibition in Antwerp:

- Lotze, K., & Meers, Ph. (2010). Citizen Heylen: Opkomst en bloei van het Rex-concern binnen de Antwerpse bioscoopsector (1950-1975). Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis, 13(2), 80-107.

- Lotze, K. (2018). Bringing the multiplex to Antwerp: A battle of two giants. TMG Journal for Media History, 21(1), 76-101.

Author

Gertjan Willems is an assistant professor at the University of Antwerp and Postdoctoral Fellow of the Research Foundation - Flanders (FWO) at Ghent University.