The Curious Case of Cinema in Ostbelgien

At the eastern border of Belgium lies a small, German-speaking region called ‘Ostbelgien’ or East Belgium. As a meeting point of German and Francophone influences, the area developed a unique culture of cinemagoing. What can the history of cinema in Ostbelgien teach us about the porousness of national borders?

By Vitus Sproten

German Speakers in Belgium

For a long time, the history of cinema has been analysed from a national perspective. The focus of these studies has usually been the question of how the history of cinema has developed in a specific national context. Belgium, with its very different cultural communities, offers a good opportunity to question this nationalistic historiography. So let’s look at the smallest, youngest, and perhaps most peculiar cultural community in Belgium: the German-speaking region.

Since the Belgian Revolution in 1830, there have been some areas in Belgium where the population spoke Plattdeutsch or Moselle Franconian dialects. These dialects are similar to the standard German language. This was the case in the so-called Arelerland around the city of Arlon as well as in the regions around the towns of Baelen, Bleyberg, and Welkenraedt. Through the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 and a controversial referendum, Belgium obtained further areas in which the German language was spoken by the majority of around 60,000 inhabitants.

A Space in Between

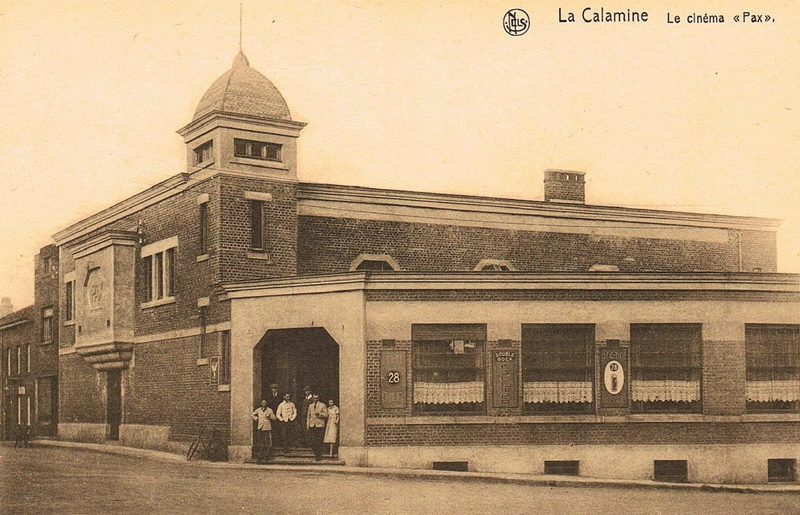

This region, known as Ostbelgien or Eupen-Malmedy, formed an area on the eastern border of Belgium that was influenced by different film cultures. It was not part of the Francophone or Flemish film culture of Belgium. It was also no longer part of the German film landscape. Accordingly, hybrid cultural constellations and experiences developed in the cinemas of the area.

The cultural and national border area took up influences from the different film cultures and adapted them to the regional circumstances. This created a cinematographic space – a ‘space in between’ – in which various cultural influences crossed, overlapped, and intermingled. The area therefore played a central role in the exchange processes between neighbouring cultures and states.

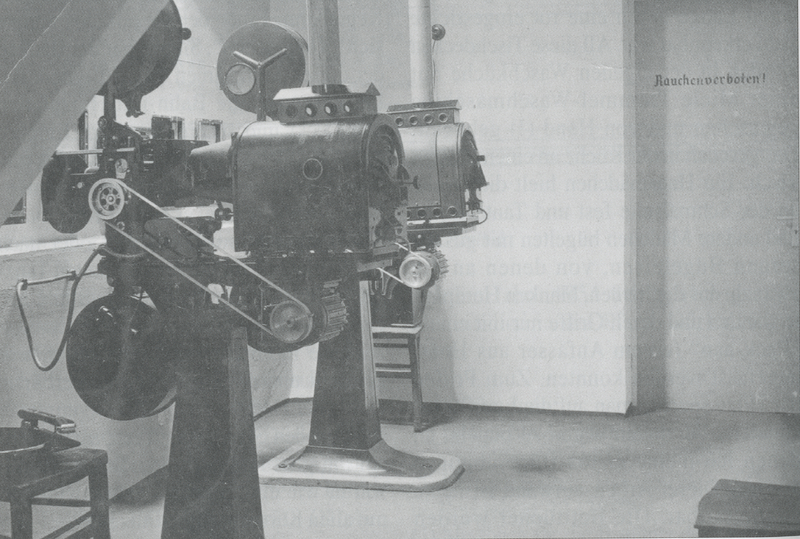

A Hybrid Cinema Landscape

These multiple influences on the region can be seen on very different levels. Politically, its film culture was shaped by the increasingly intense dichotomy between Belgium and Germany. This both reflected and intensified the internal conflicts in the region. It became particularly tangible in the 1930s, when the conflicts between democracy and dictatorship were also carried out in the area's cinemas.

In addition, linguistic influences were very important, as the cinemas in East Belgium showed films both in German and French. As in Luxembourg or Switzerland, the history of the introduction of sound film was highly influenced by the linguistic and cultural situation of the area. Whereas, among the bigger European language groups, considerable competition for American productions emerged during the early sound era, it was not per se lucrative for Belgian film distributors to acquire the rights to German sound films for the minority in the East.

Finally, cinemagoing in the region was influenced by very different film cultures. While some cinemas for instance mainly showed films and newsreels from Germany, others mainly showed movies and newsreels from France or the Anglo-Saxon world. The cultural, linguistic, and political elements were of course connected and influenced each other.

Dictatorship and Democracy

These different influences become particularly evident when we look at the period after 1933, when the National Socialists came to power in Germany. As there was no film censorship in Belgium, many Nazi propaganda films found their way into the region. At the end of the decade, propaganda films such as Ritt in die Freiheit (1936), Verräter (1936), Unternehmen Michael (1937) or films supporting the ideas of the Nazi state such as Traumulus (1935), Das Mädchen Johanna (1935), or Der höhere Befehl (1935) were shown in the cinemas of the region.

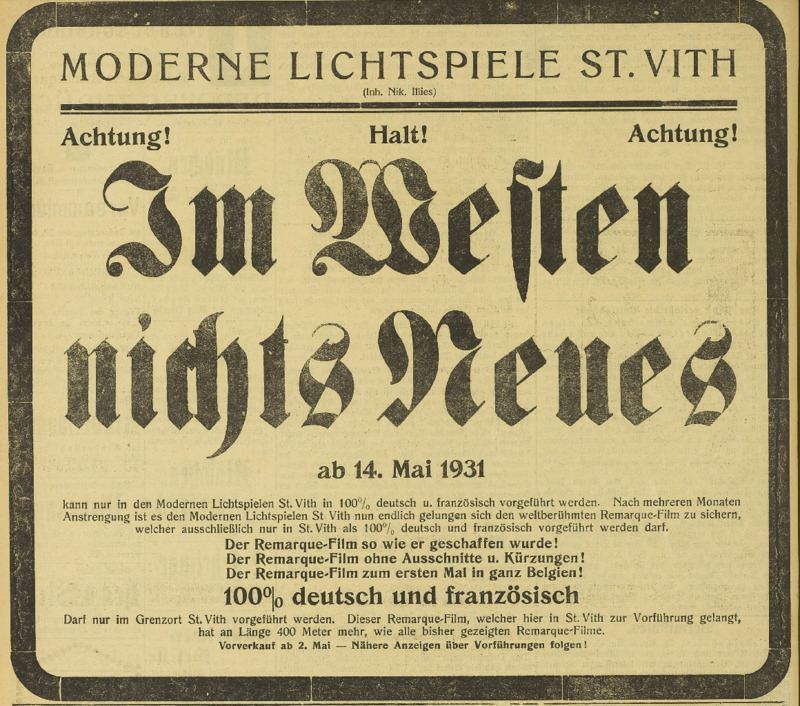

But the fact that there was no censorship in the region was also evident from another perspective. From February 1933 onwards, the Third Reich saw an increasing number of censored films ("Verboten abendfüllender Spielfilme durch Widerruf der Zulassung") and the 'Film Oberprüfstelle' (film review office) drew up a black list of 'un-German' films. The East Belgian cinemas took the bans in Germany as an occasion to show well-known but now banned films again, thus making them accessible to audiences from the neighbouring border region.

Examples of such films banned in Germany include Der Blaue Engel (The Blue Angel, 1930), Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (1931), Drei von der Tankstelle (The Three from the Filling Station, 1930), Die elf Schillschen Offiziere (The Eleven Schill Officers, 1932), Westfront 1918 (1930), and Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front, 1930). All these films were banned in Germany for different reasons and were shown again in East Belgium after their censorship.

Divided Cities

The disparate influences on cinema culture in East Belgium can also be tracked within the region’s cities. The Cinéma des Familles in Malmedy, for example, was affiliated to the Catholic pillar of Belgium and accordingly showed mainly American and French productions. The city's second cinema, the Cinéma de l'Europe, on the other hand, showed mainly German productions and was probably associated with the film distribution system of the German company Universum Film AG (UFA).

This example shows how the region between Belgium and Germany has been shaped by numerous film cultures on very different levels. These influences were of course subject to strong transformation processes. While the region was torn between Germany and Belgium in the interwar period, German film propaganda exerted its full influence in annexed Eupen-Malmedy between 1940 and 1945. After the end of the war, a special situation emerged once more. The German-speaking minority was suddenly cut off from the German film market. But how were the viewers supplied with film material? Which films did they see and in which language? An exciting story about which there is still much to discover...

Further Research

The history of cinema in the German-Belgian border region during the interwar period is now well researched. However, there are many questions that follow and should be explored in further research:

- How did different cultures and nations influence the history of cinema in other spaces, be it through distribution networks, cinema venues, or film production? Does the research for the German-speaking area in Belgium also apply to other (border) regions?

- How did cinema history develop in East Belgium during the 20th century? Did different cultural, linguistic, or national influences remain decisive for the analysis of the history of cinema in the region?

- How, in different regions of twentieth century Europe, did film distribution systems develop for groups that did not belong to the majority?

- What role does cinema play in the cultural history of a minority? Can other regions be used for comparison?

Other Sources and Data

Researchers who are interested in the (cinema) history of the German-speaking part of Belgium or other ‘spaces in between’ can also look at:

- Zentrum für Ostbelgische Geschichte: centre dedicated to the study of East Belgium, with online access to digitized historical newspapers of the region.

- Prospecting the In-Between: virtual exhibition about East Belgium that includes a large online media library.

- Impresso: digitized historical newspapers from Luxembourg and Switzerland.

Further Reading

More information about the theory of Zwischenraum (‘space in between’) can be found in:

- Brüll, C., & Fickers, A. (2017). Zeit-Räume im langen 19. Jahrhundert. Erfahrungen von Verdichtung, Beschleunigung und Beharrung. In C. Lejeune (Ed.), Grenzerfahrungen. Eine Geschichte der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft Belgiens. Vol 3: Code Civil, beschleunigte Moderne und Dynamiken des Beharrens (1794–1919) (pp. 8-27). Grenz Echo.

- Ther, P. (2003). Sprachliche, kulturelle und ethnische “Zwischenräume” als Zugang zu einer transnationalen Geschichte Europas. In P. Ther, & H. Sundhaussen (Eds.), Regionale Bewegungen und Regionalismen in europäischen Zwischenräumen seit der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts (pp. ix-xxix). Verlag Herder-Institut.

Also relevant to contextualize the case of Ostbelgien:

- Biltereyst, D., & Depauw, L. (2016). Filmcensuur in België: Over de praktijken van de Belgische filmkeuringscommissie (1922-2003). In S. Joye, D. Biltereyst, & S. Van Bauwel (Eds.), Media, democratie en identiteit. De rol van media in een democratische samenleving (pp. 133-153). Academia Press.

- Lejeune, C., Brüll, C., & Quadflieg, P. (2019). Grenzerfahrungen. Eine Geschichte der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft Belgiens. Vol. 4: Staatenwechsel, Identitätskonflikte, Kriegserfahrungen (1919–1945). Grenz Echo.

- Lesch, P. (2001). Les débuts du cinéma sonore et parlant au Luxembourg (1929-1933). Hémecht, 53(3), 293-341.

More information on the cinema history of the region:

- Beck P., Fickers, A., & Sproten V. (2018). Kino, Radio und Zeitung als Taktgeber. Information, Unterhaltung und Propaganda im Zeitalter der Massenmedien. In C. Brüll, C. Lejeune, & P. Quadflieg (Eds.), Grenzerfahrungen. Eine Geschichte der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft Belgiens. Vol 4: Staatenwechsel, Identitätskonflikte, Kriegserfahrungen (1919- 1945) (pp. 284-308). Grenz Echo.

- Sproten V. (2018). “Widerspruchsvolles Durch- und Gegeneinander.” Mediengeschichte in ländlichen Zwischenräumen – das Beispiel Eupen-Malmedy (1920-1940). In C. Zimmermann et al. (Eds.), Landmedien. Kulturhistorische Perspektiven auf das Verhältnis von Medialität und Ruralität im 20. Jahrhundert (pp. 132-157). StudienVerlag.

- Sproten V. (2020). Ein Bild und seine Geschichte (18): Happy End für das Kino in Ostbelgien?. In Zwischen Venn und Schneifel. Zeitschrift für Brauchtum und Kultur, 56(2), 37.

Author

Vitus Sproten is a researcher at the Zentrum für Ostbelgische Geschichte and the Centre for Contemporary and Digital History of the University of Luxembourg.